Researchers at ACS Central Science are reporting they can quickly detect environmentally relevant concentrations of endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs) using engineered E. coli bacteria.

EDCs have been implicated in the development of obesity, diabetes and cancer and are found in a wide array of products including pesticides, plastics and pharmaceuticals. They’re potentially harmful even at low concentrations, according to ACS Central Science, equal in some cases to mere milligrams dissolved in a swimming pool full of water.

Detecting EDCs can be tough because the classification is based on their activity — disrupting hormone function — instead of their structures. Thus, the term encompasses a broad spectrum of chemicals, and often, health risks arise from aggregate exposure to several different species.

Because many EDCs act on the same hormone receptors on a cell’s surface, researchers have been developing tests that detect the compounds based on their ability to interfere with hormones. But these methods currently take days to produce a result or involve many complicated and expensive steps. In the ACS Central Science report, Matthew Francis and colleagues overcame these challenges by using E. coli in their device.

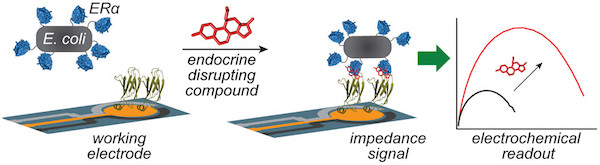

Non-toxic, dead E. coli cells display an estrogen receptor on the surface of the researchers’ portable sensor. A protein on the sensor surface recognizes the EDC-E. coli complex, producing an electronic read-out in minutes. The inexpensive device can determine the concentration of many known EDCs individually and overall concentrations as mixtures.

They tested the detection in water and in complex solutions like baby formula. It also can detect EDCs released into liquid from a plastic baby bottle following microwave heating. The team notes that their test is suitable for use in the field and can be modified to test for other types of chemicals that act on human receptors.

The authors acknowledge funding from the HoundLabs, the National Science Foundation and the Beckman Foundation.

The American Chemical Society is a nonprofit organization chartered by the U.S. Congress. With nearly 157,000 members, ACS is the world’s largest scientific society and a global leader in providing access to chemistry-related research through its multiple databases, peer-reviewed journals and scientific conferences. The American Chemical Society does not conduct research, but publishes and publicizes peer-reviewed scientific studies. Its main offices are in Washington, D.C., and Columbus, Ohio.